Eyes of the Heart presents six of Catherine Filloux’s plays.

Playwright, librettist, teacher, lecturer, and activist Catherine Filloux has been writing plays about human rights, social justice, and individual freedoms for over twenty years. Her plays often incorporate actual people and events, but are never merely biographical. By reimagining real-life characters and situations—employing temporal shifts, dreams, hallucinations, soundscapes, and other theatrical techniques—she explores the characters’ thoughts and emotions as they struggle with moral and ethical dilemmas, resist evil while searching for goodness, and react to assaults on human dignity. Her plays also question the fallibility of our collective memory, and the ways our interpretations of the past change and become distorted over time.

— From Editor’s Note

The following notes provide some historical background to the plays:

Silence of God

Silence of God opens in Cambodia in 1998, two decades after the end of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime, which killed nearly two million Cambodians and destroyed the country. In that year, Pol Pot, the regime’s supreme leader, had surfaced in the jungle district of Anlong Veng after being in hiding since 1980.

Selma ’65

In March 1965, Viola Liuzzo, a thirty-nine-year-old white woman from Michigan, was shot and killed while driving on an isolated Alabama road. Her killers were Ku Klux Klansmen who included Gary Thomas “Tommy” Rowe, an FBI undercover informant.

Mary and myra

Mary and Myra is based on Mary Todd Lincoln, the widow of Abraham Lincoln, and Myra Bradwell, a prominent women’s rights activist, editor and publisher of the Chicago Legal News, and the first woman lawyer in the U.S.

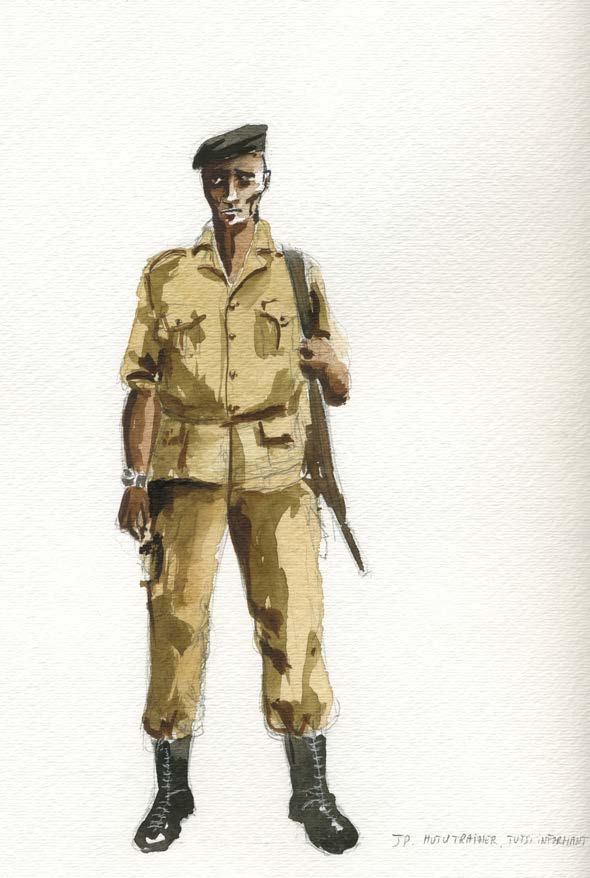

Kidnap road

In 2002, Ingrid Betancourt, a Colombian politician and activist, was driving toward the remote town of San Vicente del Caguán with her political ally Clara Rojas. A rally had been organized to support Betancourt’s bid to become the country’s president. At a roadblock, the two women were stopped, forced from their car, and kidnapped by the Marxist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). For nearly four decades, the FARC guerrillas had been rebelling against the Colombian government’s corruption and violence. By the time of the kidnapping, however, the rebels themselves had become ruthless, self-serving, and dictatorial.

Lemkin’s house

As Nazi Germany prepared to invade Eastern Europe in the 1930s, Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin anticipated the need for an internationally recognized criminal statute that would hold nations and individuals accountable for the most heinous war crime: the extermination of entire groups of people on the basis of ethnicity, religion, or race. In 1933, Germany withdrew from the League of Nations and began to overrun neighboring countries, including Poland. Lemkin joined the Polish resistance movement, was wounded, and eventually escaped to the U.S. In 1942, he became an analyst at the War Department in Washington, D.C. A year later, he learned that forty-nine members of the Lemkin family in Poland had been murdered at Treblinka. While writing a book that documented Nazi atrocities, Lemkin coined the term genocide. He would spend the rest of his life, until he died suddenly in 1959, urging nations to pass laws that would make genocide a crime punishable in international courts. .

Eyes of the heart

Lasting from 1975 to 1979, the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia was led by a man calling himself Pol Pot. Almost two million people died by execution, starvation, and torture. Those who survived witnessed and experienced atrocities that left them deeply traumatized. Two hundred thousand Cambodians fled to the U.S., and a large number of them settled in Long Beach, California. In Eyes of the Heart, Filloux brings to light a disorder that affected about 150 middle-aged and elderly Cambodian women immigrants. Though their eyes and brains were not physically injured, the women had become blind. Initially, they were accused of faking the condition. In the early 1980s, Drs. Patricia Rozee-Koker and Gretchen Van Boemel were among the first specialists to diagnose the affliction differently. Dr. Rozee-Koker concluded, “These women saw things that their minds just could not accept. Seventy percent had their immediate family killed before their eyes, so their minds simply closed down and they refused to see anymore.”

Browse full-text of Eyes of the Heart online at Project MUSE.

MĀNOA is edited by Frank Stewart and Pat Matsueda. Purchase Eyes of the Heart from UH Press or subscribe to MĀNOA: A Pacific Journal of International Writing.

MĀNOA is edited by Frank Stewart and Pat Matsueda. Purchase Eyes of the Heart from UH Press or subscribe to MĀNOA: A Pacific Journal of International Writing.