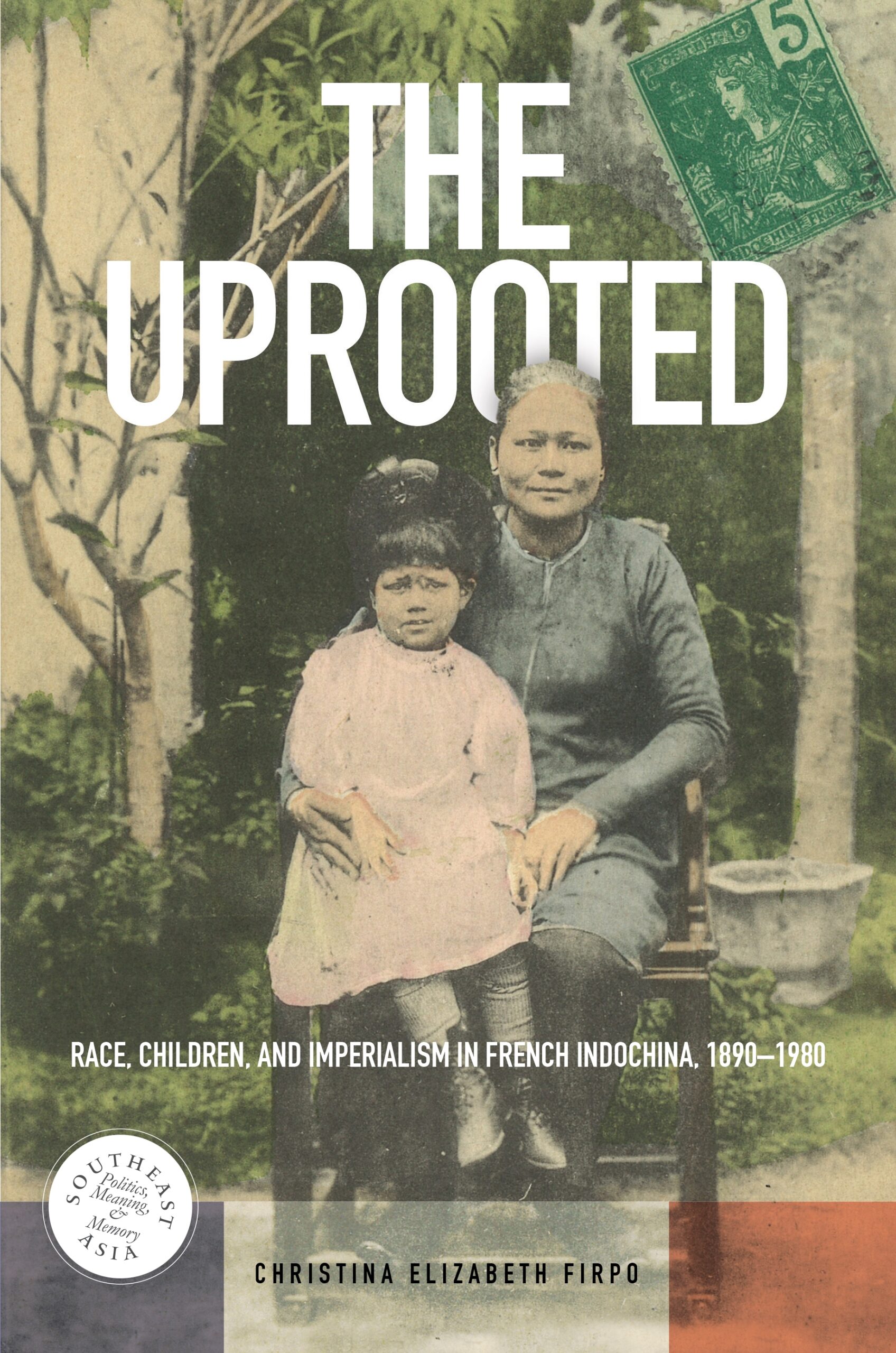

The Uprooted: Race, Children, and Imperialism in French Indochina, 1890–1980

Awards

- Winner of the International Convention of Asian Studies (ICAS) Book Prize (various categories), 2017

- About the Book

-

For over a century French officials in Indochina systematically uprooted métis children—those born of Southeast Asian mothers and white, African, or Indian fathers—from their homes. In many cases, and for a wide range of reasons—death, divorce, the end of a romance, a return to France, or because the birth was the result of rape—the father had left the child in the mother’s care. Although the program succeeded in rescuing homeless children from life on the streets, for those in their mothers’ care it was disastrous. Citing an 1889 French law and claiming that raising children in the Southeast Asian cultural milieu was tantamount to abandonment, colonial officials sought permanent, “protective” custody of the children, placing them in state-run orphanages or educational institutions to be transformed into “little Frenchmen.”

The Uprooted offers an in-depth investigation of the colony’s child-removal program: the motivations behind it, reception of it, and resistance to it. Métis children, Eurasians in particular, were seen as a threat on multiple fronts—colonial security, white French dominance, and the colonial gender order. Officials feared that abandoned métis might become paupers or prostitutes, thereby undermining white prestige. Métis were considered particularly vulnerable to the lure of anticolonialist movements—their ambiguous racial identity and outsider status, it was thought, might lead them to rebellion. Métis children who could pass for white also played a key role in French plans to augment their own declining numbers and reproduce the French race, nation, and, after World War II, empire.French child welfare organizations continued to work in Vietnam well beyond independence, until 1975. The story of the métis children they sought to help highlights the importance—and vulnerability—of indigenous mothers and children to the colonial project. Part of a larger historical trend, the Indochina case shows striking parallels to that of Australia’s “Stolen Generation” and the Indian and First Nations boarding schools in the United States and Canada. This poignant and little known story will be of interest to scholars of French and Southeast Asian studies, colonialism, gender studies, and the historiography of the family.

- About the Author(s)

-

Christina Elizabeth Firpo, Author

Christina Elizabeth Firpo is associate professor of Southeast Asian history at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo.David P. Chandler, Series Editor

Rita Smith Kipp, Series Editor

- Reviews and Endorsements

-

- The Uprooted examines how children of mixed French and Asian parentage, known as métis, were removed from their indigenous mothers and placed in institutions in French Indochina. . . . The Uprooted is a deeply engaging book that promises to stir debate on an overlooked and complex part of the intimate history of colonial Indochina. . . . This is a book worth reading both as an important chapter in the history of French Indochina and as part of a wider field of contestation over colonial cultures, race, and identity and their consequences in our own time.

—H-Asia - Examines the systematic removal and Europeanization of fatherless Eurasian children in Indochina in this easily readable and at times heartrending account of French policies that caused métis children of absent or dead French fathers to be taken away from their Vietnamese mothers and placed in French-controlled institutional settings.

—CHOICE - Overall, Firpo presents a well-written and compelling argument about the dynamics at play in French colonial society. She breaks new ground by examining the Indochina situation but follows in the footsteps of scholars who have made similar arguments in other regions. She does an exceptional job of differentiating the distinct aspects of the French experience with those of other regions experiencing similar intercultural conflicts but also demonstrates that the French colonial impulse did not markedly differ from the approach pursued by the British, the Dutch, and other European colonizers. This work is of particular utility to scholars of the civilian experience in wartime.

—H-War - Christina Firpo’s book is a remarkable achievement. It exposes a little-known history: the removal of thousands of fatherless métis children from their mothers as part of French colonial efforts in Indochina. Firpo charts the shifting symbolic value of the uprooted métis while painstakingly reconstructing the intimate lives of the children and their mothers who suffered separation. This is a haunting history beautifully wrought.

—Margaret Jacobs, author of White Mother to a Dark Race: Settler Colonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia, 1880–1940 - This compelling, well written book offers both an intellectual and social history of a neglected but important topic. Firpo reveals the depressing plight of unrecognized métis children and confronts the draconian forms of institutionalization and persistent discrimination they endured over a ninety-year period. Her rich source base, including a large trove of official archival material and period writings in French and Vietnamese, make this an important scholarly contribution.

—Peter Zinoman, author of The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862–1940

- The Uprooted examines how children of mixed French and Asian parentage, known as métis, were removed from their indigenous mothers and placed in institutions in French Indochina. . . . The Uprooted is a deeply engaging book that promises to stir debate on an overlooked and complex part of the intimate history of colonial Indochina. . . . This is a book worth reading both as an important chapter in the history of French Indochina and as part of a wider field of contestation over colonial cultures, race, and identity and their consequences in our own time.

- Supporting Resources

-