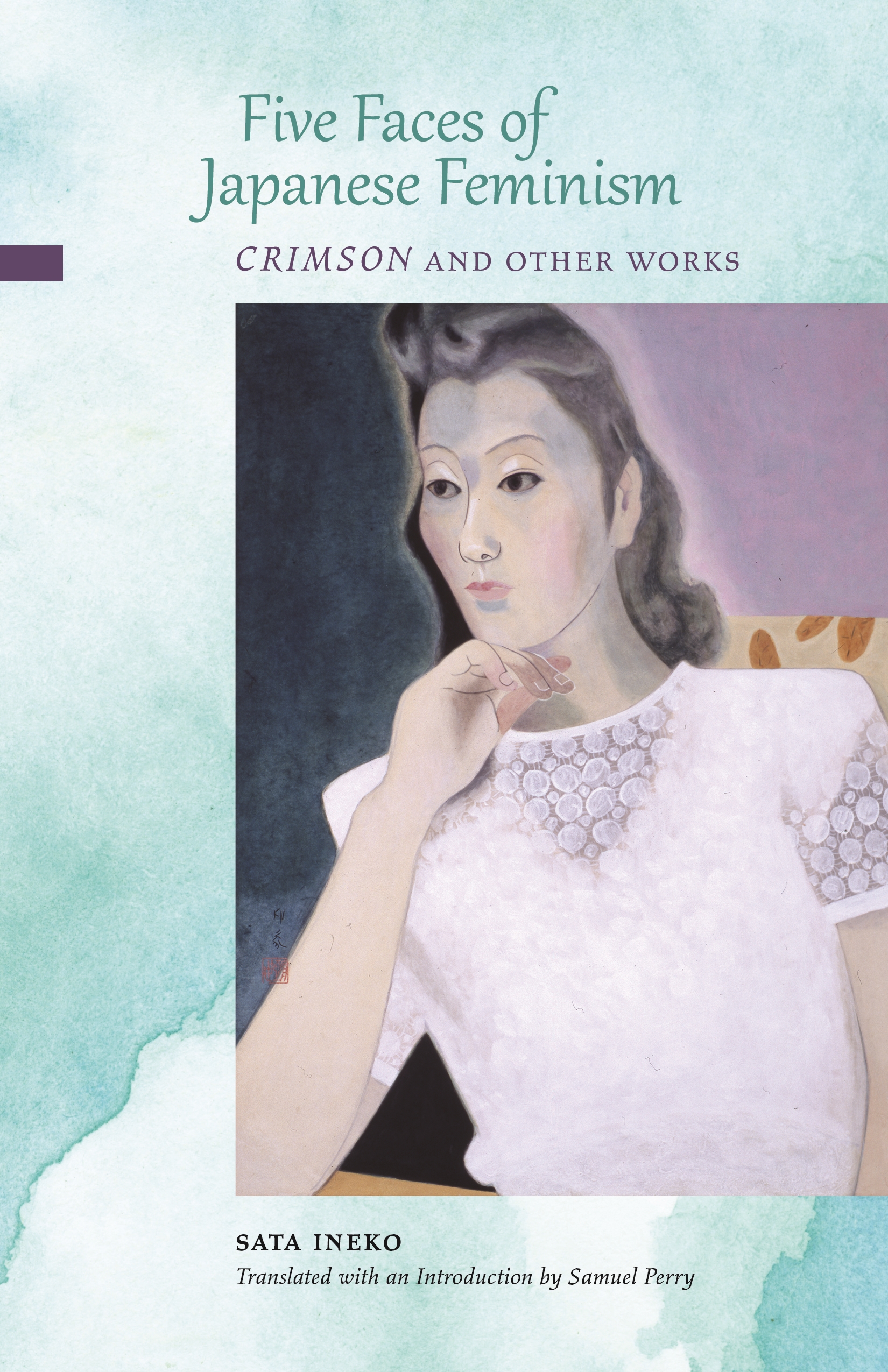

Five Faces of Japanese Feminism: Crimson and Other Works

- About the Book

-

This exquisite collection of short fiction by Sata Ineko (1904–1998) offers readers a fascinating glimpse into the lives of women rarely dignified in fiction: glamorous café waitresses, feisty communist activists, a tortured novelist, a soldier’s wife, and single women in Japan’s Korean colony. Her delicately penned portraits challenge the tired, erotic tropes of the geisha and schoolgirl, while delving into the dilemmas women themselves faced in their personal and professional relationships.

The stories and novella translated here span a period of two decades and the most important events and themes in twentieth-century history. “Café Kyoto” (1929) takes up the glamorous, if tragic, lives of café waitresses in the wake of the late 1920s Depression. “Tears of a Factory Girl in the Union Leadership” (1931) offers a unique portrait of a woman who works with the underground Communist Party. “The Scent of Incense” (1942), written as a work of “home front” literature, was meant to help mobilize women as productive workers and supportive housewives during World War II. “White and Purple” (1950), one of Sata’s rare postcolonial works penned just after the outbreak of the Korean War, reflects on the psychological damage inflicted on women during Japan’s occupation of Korea. Sata’s first novella, Crimson (1936–1938), joins a long tradition of women’s writing in Japan that sought to assert women’s “liberation” from what was seen as the oppressively patriarchal institution of marriage.

Translator Samuel Perry’s critical introduction weaves the story of Sata’s life into an examination of the historical and cultural milieu that helped to generate her stories about working women, their lives in the workplace and in the home. As the celebrated author herself once wrote, “The kinds of womanhood available today exist precisely because literary masters of different ages and cultures have drawn us to them: the woman we pity, the woman with a heart of gold, the cruel woman, the clever woman, the hen-pecker, the cheapskate, and the ‘good wife wise mother.’ As terms we use to describe the kinds of women who exist in the world today, they have simply outgrown their usefulness.”

- About the Author(s)

-

Ineko Sata, Author

Sata Ineko (1904–1998) was one of the most prominent and prolific writers of twentieth-century Japan.Samuel Perry, Translator

Samuel Perry is associate professor of East Asian studies at Brown University.

- Reviews and Endorsements

-

- From child laborer to Communist, from wartime apologist to celebrated writer, Sata Ineko infuses her stories with her richly diverse experiences. This collection, masterfully selected and translated by Samuel Perry, is a wonderful introduction to her brave spirit and her commitment to the proletarian voice, offering readers an intimate look into the trials, turmoil, and occasional triumphs attending the life of this exceptional woman.

—Rebecca Copeland, professor of Japanese literature, Washington University in St. Louis - A recent explosion of scholarship on Japan’s “red decade” is transforming our perspectives on the lived experiences of the Japanese twentieth century. Five Faces of Japanese Feminism, a collection of stories by the prolific leftist writer Sata Ineko, makes a signal contribution to that transformation. Translated and with an illuminating introduction by Samuel Perry, Sata’s stories strive toward representation of the intersecting economic, political, and affective dimensions of modern Japanese women’s lives rather than their aestheticization. In a series of works ranging from early experimental to more mature texts—set against the backdrops of Japan’s rapid industrialization, urbanization, imperial wars, and their aftermath—we find Sata’s fiction as intensely concerned with the day-to-day details of her women characters’ struggle for independence as it is with their oppression.

—Brett de Bary, professor of Asian studies and comparative literature, Cornell University

- From child laborer to Communist, from wartime apologist to celebrated writer, Sata Ineko infuses her stories with her richly diverse experiences. This collection, masterfully selected and translated by Samuel Perry, is a wonderful introduction to her brave spirit and her commitment to the proletarian voice, offering readers an intimate look into the trials, turmoil, and occasional triumphs attending the life of this exceptional woman.

- Supporting Resources

-